|

| 1 | +# The page cache |

| 2 | + |

| 3 | +Source: |

| 4 | + |

| 5 | +- <https://notes.eddyerburgh.me/operating-systems/linux/the-page-cache-and-page-writeback> |

| 6 | +- <https://biriukov.dev/docs/page-cache/0-linux-page-cache-for-sre/> |

| 7 | + |

| 8 | +Table of contents: |

| 9 | + |

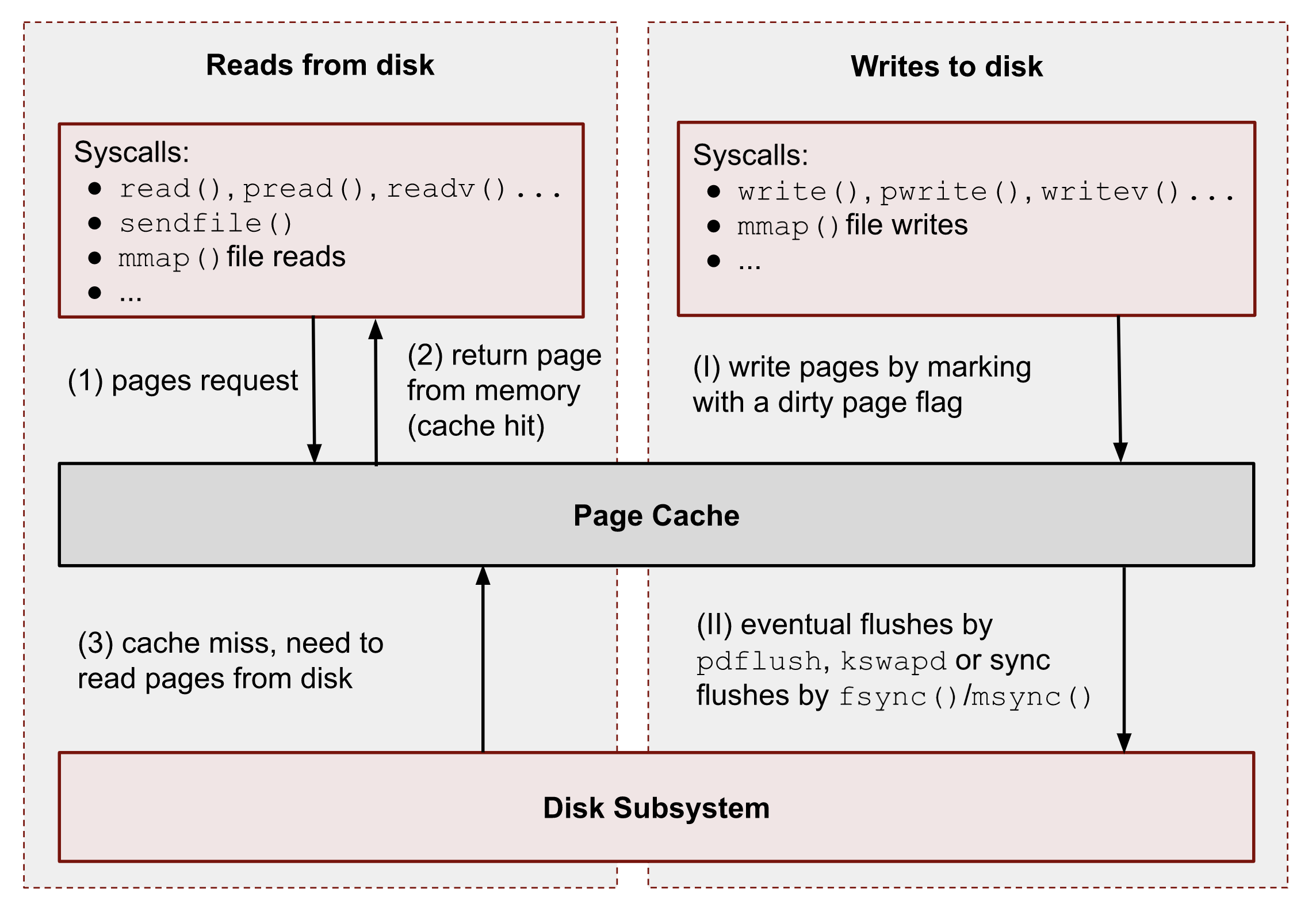

| 10 | +The page cache is a disk cache used to minimize disk I/O. Instead of read requests and write operations running against a disk, they run against an in-memory cache (unused areas of the memory) that only reads data from disk when needed and writes changes to disk periodically. |

| 11 | + |

| 12 | +The page cache contains physical pages in RAM, which correspond to physical blocks on a disk. The page cache is dynamic: “it can grow to consume any free memory and shrink to relieve memory pressure”. |

| 13 | + |

| 14 | +“Page” in the Page Cache means that linux kernel works with memory units called pages. It would be cumbersome and hard to track and manage bites or even bits of information. So instead, Linux’s approach (and not only Linux’s, by the way) is to use pages (usually 4K in length) in almost all structures and operations. Hence the minimal unit of storage in Page Cache is a page, and it doesn’t matter how much data you want to read or write. All file IO requests are aligned to some number of pages. |

| 15 | + |

| 16 | +The above leads to the important fact that if your write is smaller than the page size, the kernel will read the entire page before your write can be finished. |

| 17 | + |

| 18 | + |

| 19 | + |

| 20 | +## 1. Approaches to caching |

| 21 | + |

| 22 | +### 1.1. Read strategy |

| 23 | + |

| 24 | +Generally speaking, reads are handled by the kernel in the following way: |

| 25 | + |

| 26 | +① – When a user-space application wants to read data from disks, it asks the kernel for data using special system calls such as `read()`, `pread()`, `vread()`, `mmap()`, `sendfile()`, etc. |

| 27 | + |

| 28 | +② – Linux kernel, in turn, checks whether the pages are present in Page Cache and immediately returns them to the caller if so. As you can see kernel has made 0 disk operations in this case. |

| 29 | + |

| 30 | +③ – If there are no such pages in Page Cache, the kernel must load them from disks. In order to do that, it has to find a place in Page Cache for the requested pages. A memory reclaim process must be performed if there is no free memory (in the caller’s cgroup or system). Afterward, kernel schedules a read disk IO operation, stores the target pages in the memory, and finally returns the requested data from Page Cache to the target process. Starting from this moment, any future requests to read this part of the file (no matter from which process or cgroup) will be handled by Page Cache without any disk IOP until these pages have not been evicted. |

| 31 | + |

| 32 | +### 1.2. Write strategy |

| 33 | + |

| 34 | +Let’s repeat a step-by-step process for writes: |

| 35 | + |

| 36 | +① – When a user-space program wants to write some data to disks, it also uses a bunch of syscalls, for instance: `write()`, `pwrite()`, `writev()`, `mmap()`, etc. The one big difference from the reads is that writes are usually faster because real disk IO operations are not performed immediately. However, this is correct only if the system or a cgroup doesn’t have memory pressure issues and there are enough free pages (we will talk about the eviction process later). So usually, the kernel just updates pages in Page Cache. it makes the write pipeline asynchronous in nature. The caller doesn’t know when the actual page flush occurs, but it does know that the subsequent reads will return the latest data. Page Cache protects data consistency across all processes and cgroups. Such pages, that contain un-flushed data have a special name: dirty pages. |

| 37 | + |

| 38 | +② – If a process’ data is not critical, it can lean on the kernel and its flush process, which eventually persists data to a physical disk. But if you develop a database management system (for instance, for money transactions), you need write guarantees in order to protect your records from a sudden blackout. For such situations, Linux provides `fsync()`, `fdatasync()` and `msync()` syscalls which block until all dirty pages of the file get committed to disks. There are also `open()` flags: `O_SYNC` and `O_DSYNC`, which you also can use in order to make all file write operations durable by default. I’m showing some examples of this logic later. |

| 39 | + |

| 40 | +There are three strategies for implementing write requests with caches: |

| 41 | + |

| 42 | +- No-write—the write request updates the data on disk, and the cache is invalidated. |

| 43 | +- Write-through—the write request updates the data on disk and in the cache. |

| 44 | +- Write-back—the write request updates the data in the cache and updates the data on disk in the future. |

| 45 | + |

| 46 | +Linux uses the write-back strategy. Write requests update the cached data. The updated pages are then marked as dirty, and added to the dirty list. A process then periodically updates the blocks corresponding to pages in the dirty list. |

| 47 | + |

| 48 | +### 1.3. Cache eviction |

| 49 | + |

| 50 | +- Removing items from the cache is known as cache eviction. This is done to either make room for more relevant data, or to shrink it in order to free memory. |

| 51 | +- Linux cache eviction works by removing only clean pages. It uses a variation of the LRU (Least Recently Used) algorithm, the two-list strategy. |

| 52 | +- In the two-list strategy, Linux maintains two linked lists: the active list and the inactive list. Pages on the active list are considered hot and are not available for eviction. Pages on the inactive list are available for eviction. Pages are placed on the active list if they are already residing in the inactive list [1, P. 325]. |

| 53 | +- The lists are maintained in a pseudo-LRU manner. Items are added to the tail, and are removed from the head. If the active list grows much larger than the inactive list, items are moved back from the active list to the inactive list. |

| 54 | + |

| 55 | +## 2. The Flusher Threads |

| 56 | + |

| 57 | +The flusher threads periodically write dirty pages to disk. There are three situations that cause writes: |

| 58 | + |

| 59 | +- When free memory shrinks below a predefined threshold. |

| 60 | +- When dirty data grows older than a specific threshold. |

| 61 | +- When a user process calls the `sync()` or `fsync()` system calls. |

| 62 | + |

| 63 | +When free memory shrinks below the threshold (defined by the `dirty_background_ratio` sysctl), the kernel invokes `wakeup_flusher_threads()` to wake up one or more flusher threads to run `bdi_writeback_all()`. `bdi_writeback_all()` takes the number of pages to write-back as a parameter. It will continue writing back pages until either the free memory is above the `dirty_background_ratio` threshold, or until the minimum number of pages has been written out. |

| 64 | + |

| 65 | +To ensure dirty data doesn’t grow older than a specific threshold, a kernel thread periodically wakes up and writes out old dirty pages |

| 66 | + |

| 67 | +## 3. Page cache and basic file operations |

| 68 | + |

| 69 | +```shell |

| 70 | +$ dd if=/dev/random of=/var/tmp/file1.db count=128 bs=1M |

| 71 | +``` |

| 72 | + |

| 73 | +### 3.1. File reads |

| 74 | + |

| 75 | +- Reading files with `read()` syscall. |

| 76 | + |

| 77 | +```python |

| 78 | +with open("/var/tmp/file1.db", "br") as f: |

| 79 | + print(f.read(2)) |

| 80 | +``` |

| 81 | + |

| 82 | +```shell |

| 83 | +$ strace -s0 python3 ./read_2_bytes.py |

| 84 | +# read syscall returned 4096 bytes (one page) even though the script asked only for 2 bytes. |

| 85 | + |

| 86 | +# Check how much data the kernel's cached |

| 87 | +$ vmtouch /var/tmp/file1.db |

| 88 | + Files: 1 |

| 89 | + Directories: 0 |

| 90 | + Resident Pages: 128/32768 512K/128M 0.391% |

| 91 | + Elapsed: 0.000698 seconds |

| 92 | +# The kernel has cached 512KiB or 128 pages |

| 93 | +``` |

| 94 | + |

| 95 | +- By design, the kernel can't load anything less than 4KiB or one page into Page cache, but what about the other 127 pages? It's called **read ahead** logic and preference to perform sequential IO operations over random ones. The basic idea is to **predict the subsequent reads and minimize the number of disks seeks** (`man 2 readahead` and `man 2 posix_fadvise`). |

| 96 | +- Use `posix_fadvise()` to notify the kernel that we're reading the file randomly, and thus we don't want to have any ahead features: |

| 97 | + |

| 98 | +```python |

| 99 | +import os |

| 100 | + |

| 101 | +with open("/var/tmp/file1.db", "br") as f: |

| 102 | + fd = f.fileno() |

| 103 | + os.posix_fadvise(fd, 0, os.fstat(fd).st_size, os.POSIX_FADV_RANDOM) |

| 104 | + print(f.read(2)) |

| 105 | +``` |

| 106 | + |

| 107 | +```shell |

| 108 | +$ echo 3 | sudo tee /proc/sys/vm/drop_caches && python3 ./read_2_random.py |

| 109 | +3 |

| 110 | +b'\xf5\xf2' |

| 111 | + |

| 112 | +$ vmtouch /var/tmp/file1.db |

| 113 | + Files: 1 |

| 114 | + Directories: 0 |

| 115 | + Resident Pages: 1/32768 4K/128M 0.00305% |

| 116 | + Elapsed: 0.000376 seconds |

| 117 | +``` |

| 118 | + |

| 119 | +- Reading files with `mmap()` syscall: it's a "magic" tool and can be used to solve a wide range and can be used to solve a wide range of tasks. |

| 120 | + |

| 121 | +```python |

| 122 | +import mmap |

| 123 | + |

| 124 | +with open("/var/tmp/file1.db", "r") as f: |

| 125 | + with mmap.mmap(f.fileno(), 0, prot=mmap.PROT_READ) as mm: |

| 126 | + print(mm[:2]) |

| 127 | +``` |

| 128 | + |

| 129 | +```shell |

| 130 | +$ echo 3 | sudo tee /proc/sys/vm/drop_caches && python3 ./read_2_mmap.py |

| 131 | + |

| 132 | +$ vmtouch /var/tmp/file1.db |

| 133 | + Files: 1 |

| 134 | + Directories: 0 |

| 135 | + Resident Pages: 32/32768 128K/128M 0.0977% |

| 136 | + Elapsed: 0.00056 seconds |

| 137 | +``` |

| 138 | + |

| 139 | +- Let's change the readahead with `madvise()` syscall like we did with `fadvise()`. |

| 140 | + |

| 141 | +```python |

| 142 | +import mmap |

| 143 | + |

| 144 | +with open("/var/tmp/file1.db", "r") as f: |

| 145 | + with mmap.mmap(f.fileno(), 0, prot=mmap.PROT_READ) as mm: |

| 146 | + mm.madvise(mmap.MADV_RANDOM) |

| 147 | + print(mm[:2]) |

| 148 | +``` |

| 149 | + |

| 150 | +```shell |

| 151 | +$ echo 3 | sudo tee /proc/sys/vm/drop_caches && python3 ./read_2_mmap_random.py |

| 152 | + |

| 153 | +$ vmtouch /var/tmp/file1.db |

| 154 | + Files: 1 |

| 155 | + Directories: 0 |

| 156 | + Resident Pages: 1/32768 4K/128M 0.00305% |

| 157 | + Elapsed: 0.00052 seconds |

| 158 | +``` |

| 159 | + |

| 160 | +### 3.2. File writes |

| 161 | + |

| 162 | +- Writing to files with `write()` syscall. |

| 163 | + |

| 164 | +```python |

| 165 | +with open("/var/tmp/file1.db", "br+") as f: |

| 166 | + print(f.write(b"ab")) |

| 167 | +``` |

| 168 | + |

| 169 | +```shell |

| 170 | +$ sync; echo 3 | sudo tee /proc/sys/vm/drop_caches && python3 ./write_2_bytes.py |

| 171 | + |

| 172 | +$ vmtouch /var/tmp/file1.db |

| 173 | + Files: 1 |

| 174 | + Directories: 0 |

| 175 | + Resident Pages: 130/32768 520K/128M 0.397% |

| 176 | + Elapsed: 0.0004 seconds |

| 177 | +``` |

| 178 | + |

| 179 | +- Check dirty pages by reading the current cgroup memory stat file. |

| 180 | + |

| 181 | +```shell |

| 182 | +$ cat /proc/self/cgroup |

| 183 | +0::/user.slice/user-1000.slice/session-c2.scope |

| 184 | + |

| 185 | +$ grep dirty /sys/fs/cgroup/user.slice/user-1000.slice/session-c2.scope/memory.stat |

| 186 | +file_dirty 102400 |

| 187 | +``` |

| 188 | + |

| 189 | +- File writes with `mmap()` syscall. |

| 190 | + |

| 191 | +```python |

| 192 | +import mmap |

| 193 | + |

| 194 | +with open("/var/tmp/file1.db", "r+b") as f: |

| 195 | + with mmap.mmap(f.fileno(), 0) as mm: |

| 196 | + mm[:2] = b"ab" |

| 197 | +``` |

| 198 | + |

| 199 | +```shell |

| 200 | +$ sync; echo 3 | sudo tee /proc/sys/vm/drop_caches && python3 ./write_mmap.py |

| 201 | + |

| 202 | +$ vmtouch /var/tmp/file1.db |

| 203 | + Files: 1 |

| 204 | + Directories: 0 |

| 205 | + Resident Pages: 120/32768 480K/128M 0.366% |

| 206 | + Elapsed: 0.000705 seconds |

| 207 | +``` |

| 208 | + |

| 209 | +- If your program uses `mmap()` to write to files, you have one more option to get dirty pages stats with a per-process granularity. `procfs` has the `/proc/PID/smaps` file. It contains memory counters for the process broken down by virtual memory areas (VMA). We can get dirty pages by finding: |

| 210 | + - `Private_Dirty` – the amount of dirty data this process generated; |

| 211 | + - `Shared_Dirty` – and the amount other processes wrote. This metric shows data only for referenced pages. It means the process should access pages and keep them in its page table. |

| 212 | + |

| 213 | +### 3.3. Synchronize file changes with `fsync()`, `fdatasync()`, and `msync()` |

0 commit comments