This field manual provides a tactical overview of applying the theoretical frameworks of Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari (henceforth known as D&G) to the practice of DevOps. Drawing from their concepts of assemblage, territory, lines of flight, desiring-production, rhizome, body without organs, the schizophrenic anti-oedijus, amongst other theories, this manual outlines how to reconfigure traditional development and operations workflows to foster fluidity, adaptability, and collective intelligence in complex, dynamic environments.

The manual is structured to mirror the principles of agile warfare, emphasizing decentralized decision-making, continuous adaptation, and the creation of smooth spaces of collaboration. It is intended for use by DevOps practitioners, operators, engineers, team leads, and organizational strategists seeking to implement a more flexible and responsive operational framework, and tasked vith navigating the complex, ever-evolving landscape of product delivery and system maintenance.

By adopting a rhizomatic approach, teams can break away from rigid, hierarchical structures and embrace a more fluid, adaptive, collaborative workflow, and interconnected systems capable responding to change with speed and precision.

The following sections will provide actionable strategies, tactical insights, and doctrinal principles for integrating these philosophical concepts into your DevOps operations, from planning to deployment and beyond.

The ancient Greeks thought that atoms were it. ἄτομος, Wikipedia will tell you, comes from ‘ἀ’- meaning “not” and ‘τέμνω’, meaning ‘I cut.’ Cells are the smallest thing that there is. You can’t cut them in half. Everything is composed of a bunch of atoms.

Well, guess what? Modern science has found things smaller than atoms. Dammit! What we do know for sure, though, is that some things are made up of composites of other things. That’s for sure. We’re still not clear on what that fundamental stuff is, but composites are a pretty safe bet. Even if atoms are made up of other things, we know that other things are made up of a bunch of atoms.

So how can we talk about composites? Well, a programmer’s fundamental tool is abstraction. So we can black-box any particular composite and treat it as a whole entity, without worrying about what we’ve encapsulated inside. That’s good, and that’s useful, but there’s a problem: when you start thinking of a collection of things as just one thing, you miss out on a lot of important details. As we know, all abstractions are leaky, so how does a black box leak?

Let’s think about your body: it’s a composite, you’re made up of (among other things) a whole pile of organs, and one (skin) wrapping the rest of them up in a nice black box. If we had lived a few hundred years ago, thinking of the body as a black box would be a pretty fair metaphor: after all, if you take out someone’s heart, they die. The box needs all of its parts inside. Today, though, that’s not true: we can do heart transplants. Further, we have artificial hearts. A person with an artificial heart is not the exact same as a person without one, yet they are both still people. Thinking of a body as a totality leaks as an abstraction in modern times.

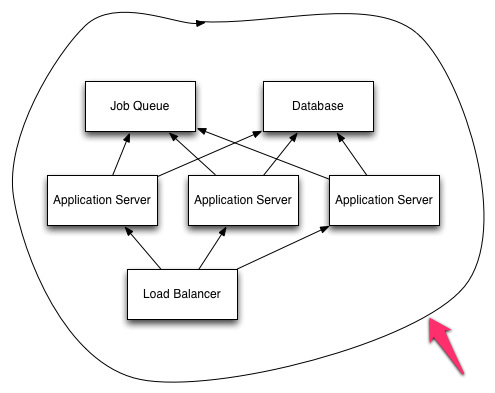

Let’s move away from biology for a bit and into web applications instead. Here’s an architecture diagram of a typical web service:

Looks pretty normal, right? Let’s modify it a bit:

This is the same web service, right? We’ve introduced a few database slaves and a reverse proxy, which allowed us to knock out one of our application servers. In a certain sense, this service is equivalent; in another, it’s different: It’s got another extra component, and one component has developed more complexity. We might need to hire a DBA and someone who’s good at writing Varnish configs. Different skills are needed.

So what do we call this thing? An ‘assemblage.’ It’s made up of smaller assemblages as well; after all, our application servers may use the Reactor pattern, the worker model of Unicorn, or the threaded model of the JVM. To quote Levi Bryant, “Assemblages are composed of heterogeneous elements or objects that enter into relations with one another.” In the body metaphor, these are organs, and in the systems diagram, they’re the application servers, databases, and job queues. Assemblages are also ‘objects’ in this context, so you can think of any of those objects as being made up of other ones. But to think of the formations of objects as a total whole or black box is incorrect, or at best, a leaky abstraction.

Let’s get at one other excellent example of an assemblage: the internet. Computers connect, disconnect, reconnect. They may be here one moment, gone the next, or stay for an extended period of time. The internet isn’t any less an internet when you close your laptop and remove it, nor when you add a new server onto your rack. Yet we still talk about it as though it were a whole. It’s not, exactly: it’s an assemblage.

Furthermore, there’s a reason that Bryant uses the generic ‘objects’ or ‘elements’ when talking about assemblages: objects can be ‘people’ or ‘ideas’ as well as physical parts. This is where the ‘systems’ idea of computer science diverges from ‘assemblage’: depending on how you want to analyze things, your users may be part of an assemblage diagram as well.

So what’s the point? Well, this is a basic term that can be used to think about problems. A design pattern of thought. A diagram. In future posts, I’ll actually use this pattern to address a particular problem, but you need to understand the pattern before you can understand how it’s used.

(and to give you a comparison of complexity of explanation, here’s the blog post by on assemblages where I got that quote from. He quotes Deleuze directly and extensively:

by Levi Bryant

In preparing my talk on Deleuze’s overturning of Platonism and his theory of simulacra for the RMMLA on Friday, I came across the following terrific interview with Deleuze on A Thousand Plateaus and assemblages:

If there is no single field to act as a foundation, what is the unity of A Thousand Plateaus?

I think it is the idea of an assemblage (which replaces the idea of desiring machines). There are various kinds of assemblages, and various component parts. On the one hand, we are trying to substitute the idea of assemblage for the idea of behavior: whence the importance of ethology, and the analysis of animal assemblages, e.g., territorial assemblages. The chapter on the Ritornello, for example, simultaneously examines animal assemblages and more properly musical assemblages: this is what we call a “plateau,” establishing a continuity between the ritornellos of birds and Schumann’s ritornellos. On the other hand, the analysis of assemblages, broken down into their component parts, opens up the way to a general logic: Guattari and I have only begun, and completing this logic will undoubtedly occupy us in the future. Guattari calls it “diagrammatism.” In assemblages you you find states of things, bodies, various combinations of bodies, hodgepodges; but you also find utterances, modes of expression, and whole regimes of signs. The relations between the two are pretty complex. For example, a society is defined not by productive forces and ideology, but by “hodgepodges” and “verdicts.” Hodgepodges are combinations of interpenetrating bodies. These combinations are well-known and accepted (incest, for example, is a forbidden combination). Verdicts are collective utterances, that is, instantaneous and incorporeal transformations which have currency in a society (for example, “from now on you are no longer a child”…).

These assemblages which you are describing, seems to me to have value judgments attached to them. Is this correct? Does A Thousand Plateaus have an ethical dimension?

Assemblages exist, but they indeed have component parts that serve as criteria and allow the various assemblages to be qualified. Just as in painting, assemblages are a bunch of lines. But there are all kinds of lines. Some lines are segments, or segmented; some lines get caught in a rut, or disappear into “black holes”; some are destructive, sketching death; and some lines are vital and creative. These creative and vital lines open up an assemblage, rather than close it down. The idea of an “abstract” line is particularly complex. A line may very well represent nothing at all, be purely geometrical, but it is not yet abstract as long as it traces an outline. An abstract line is a line with no outlines, a line that passes between things, a line in mutation. Pollock’s line has been called abstract. In this sense, an abstract line is not a geometrical line. It is very much alive, living and creative. Real abstraction is non-organic life. This idea of nonorganic life is everywhere in A Thousand Plateaus and this is precisely the life of the concept. An assemblage is carried along by its abstract lines, when it is able to have or trace abstract lines. You know, it’s curious, today we are witnessing the revenge of silicon. Biologists have often asked themselves why life was “channeled” through carbon rather than silicon. But the life of modern machines, a genuine non-organic life, totally distinct from the organic life of carbon, is channeled through silicon. This is the sense in which we speak of a silicon-assemblage. In the most diverse fields, one has to consider the component parts of assemblages, the nature of the lines, the mode of life, the mode of utterance…

In reading your work, one gets the feeling that those distinctions which are traditionally most important have disappeared: for instance, the distinction between nature and culture; or what about epistemological distinctions?

There are two ways to supress or attenuate the distinction between nature and culture. The first is to liken animal behavior to human behavior (Lorenz tried it, with disquieting political implications). But what we are saying is that the idea of assemblages can replace the idea of behavior, and thus with respect to the idea of assemblage, the nature-culture distinction no longer matters. In a certain way, behavior is still a countour. But an assemblage is first and foremost what keeps very heterogeneous elements together: e.g. a sound, a gesture, a position, etc., both natural and artificial elements. The problem is one of “consistency” or “coherence,” and it prior to the problem of behavior. How do things take on consistency? How do they cohere? Even among very different things, an intensive continuity can be found. We have borrowed the word “plateau” from Bateson precisely to designate these zones of intensive continuity. (Two Regimes of Madness, pgs. 176 – 179)

I take three key points from this interview:

-

Assemblages are composed of heterogeneous elements or objects that enter into relations with one another. These objects are not all of the same type. Thus you have physical objects, happenings, events, and so on, but you also have signs, utterances, and so on. While there are assemblages that are composed entirely of bodies, there are no assemblages composed entirely of signs and utterances.

-

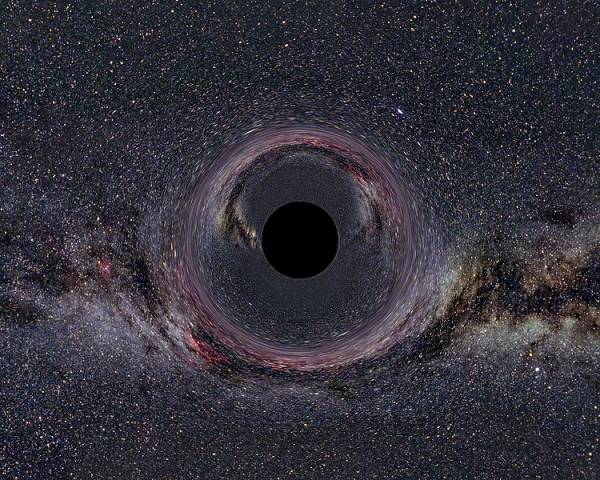

I think the idea of different kinds of lines is particularly fruitful. This is especially the case of those lines that tend towards ruts, black holes, and death. Posts about minotaurs, trolls, and gray vampires are really posts about black holes. The black hole or, as Einstein called it “dark star”, is an entity whose gravitational force is so strong that nothing, not even light, can escape from it. Minotauring, trolling, and gray vampiring are forms of engagement that suck all discussion into their orbit, preventing it from moving on. As such, they tend to prevent the formation of assemblages. One aim in cultivating and evaluating assemblages lies in finding ways to escape ruts, black holes, and lines leading to death.

-

Deleuze’s claims about coherency and consistency are particularly important. Consistency and coherence are not qualities that precede assemblages, rather they are emergent properties that do or do not arise from assemblage. It is noteworthy that the term “consistency” is not being used in the logical sense, but in the sense of solutions and substances. Deleuze and Guattari’s notion of consistency is closer to the way we use it when talking about cement, referring to it as “soupy”, “dry”, “lumpy”, “coarse”, “consisting of stone and lime”, etc., than the logical sense of “lacking in contradictions”. An assemblage can be riddled with contradictions as in the case of the economic and ethnic divisions that divide the North and South side of Chicago, while still producing consistency and coherence. Consistency and coherence are thus not about being without logical contradiction, nor about harmony, but rather about how heterogeneous elements or objects hang together.

Let’s re-examine this diagram of the assemblage:

What’s up with this line?

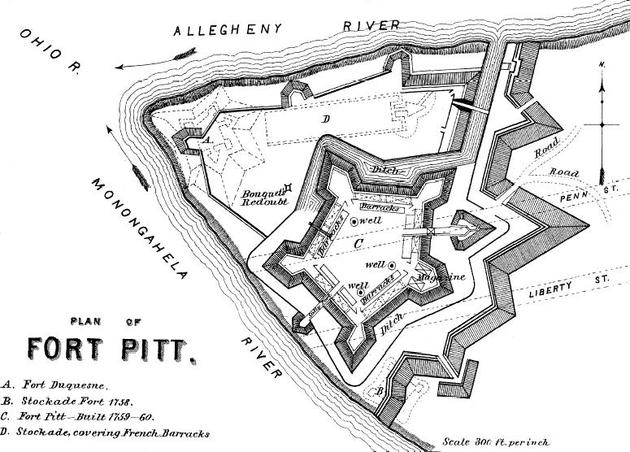

Well, just because assemblages are amorphous doesn’t mean that there’s no way to demarcate what’s in the assemblage and what is not. This particular assemblage has a ‘territory,’ of sorts: everything that’s inside the line is part of the territory, and everything that’s not is outside. Think of a fort, or a castle: