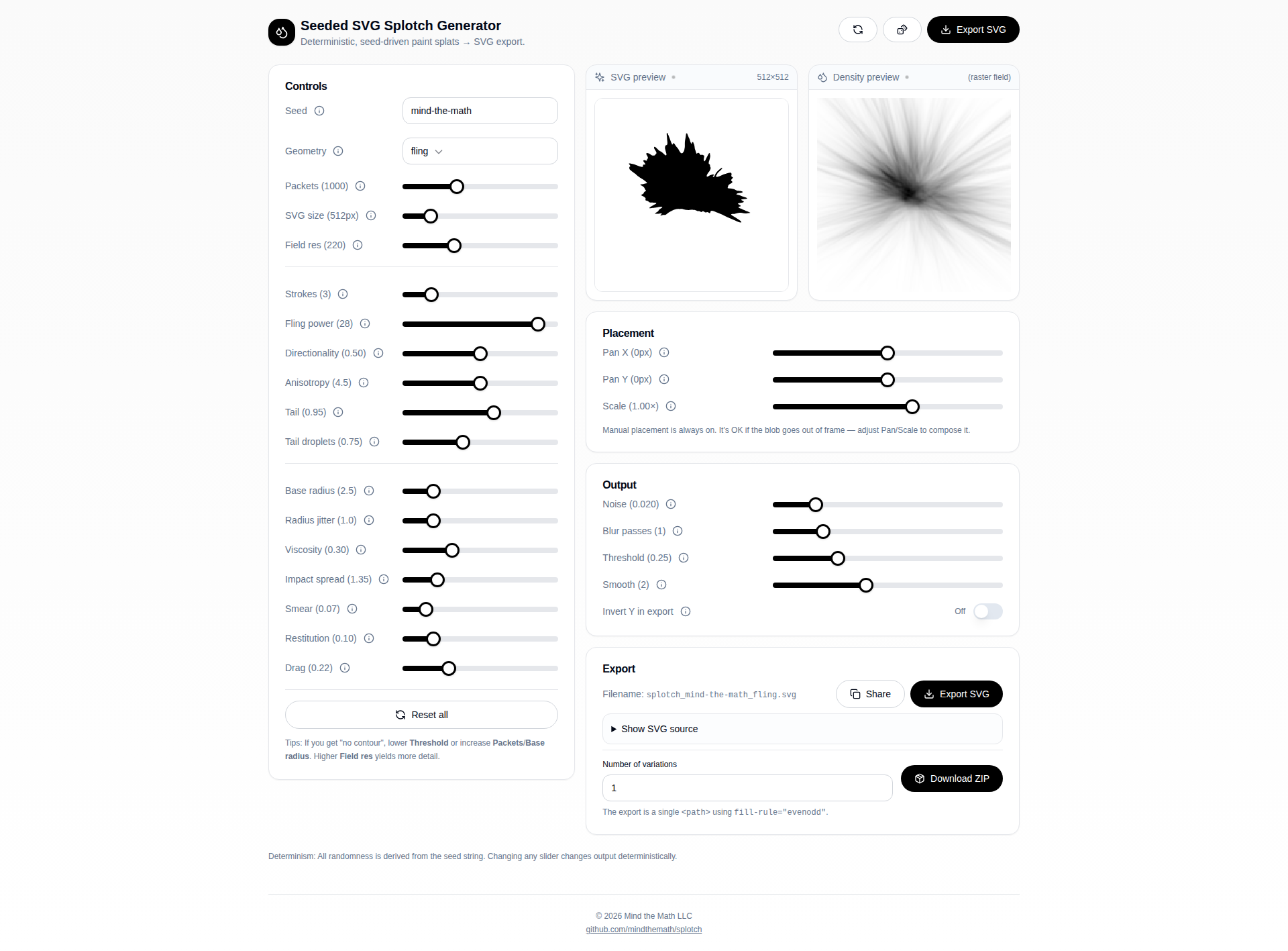

A deterministic, seed-driven paint splat generator that creates SVG blob shapes through physics-based simulation.

Since you have Bun installed, you can run the app with:

# Install dependencies (if you haven't already)

bun install

# Start the development server

bun run devThe app will be available at http://localhost:5173 (or the port shown in the terminal).

The app supports sharing complete configurations via URL parameters. All slider values and settings (except export-specific options like filename and variations count) are encoded in the URL.

Click the Share button (with the copy icon) in the Export section to copy a URL containing all current settings. When someone opens that URL, the app will automatically restore all parameters.

Parameters use short names to keep URLs manageable. All parameters are included in the URL (defaults are not omitted to ensure compatibility if defaults change).

| Short Name(s) | Full Name | Description |

|---|---|---|

s, seed |

seed |

Deterministic seed string |

g, geom, geometry |

geometry |

Geometry mode: circle, line, spray, or fling |

sz |

svgSize |

SVG export size in pixels |

fs |

fieldSize |

Internal simulation grid resolution |

p |

packets |

Number of paint packets simulated |

br |

baseRadius |

Typical droplet radius |

rj |

radiusJitter |

Random variation in droplet size |

v |

viscosity |

Paint viscosity (resists flow) |

r |

restitution |

Bounciness / secondary rebounds |

d |

drag |

Air resistance during flight |

is |

impactSpread |

Distance micro-droplets travel on impact |

sm |

smear |

Radial outward smear during slide |

n |

noise |

Randomness added to density field |

b |

blur |

Post-blur passes on density field |

t |

threshold |

Contour cutoff value |

smth |

smooth |

Chaikin smoothing iterations |

sa |

sprayAngleDeg |

Direction angle in degrees (0-360) |

smag |

sprayMagnitude |

Strength of directional drift |

sc |

sprayCovariance |

Anisotropy of spray cloud |

st, strokes |

strokes |

Number of fling strokes |

fp |

flingPower |

How hard paint is thrown |

dir |

directionality |

Alignment tightness for fling |

an |

anisotropy |

Elongation along velocity |

tl |

tail |

Surface streaking length |

td |

tailDroplets |

Probability of far droplets |

px |

panX |

Horizontal pan offset (pixels) |

py |

panY |

Vertical pan offset (pixels) |

us |

userScale |

Scale multiplier |

iy |

invertY |

Invert Y axis (0 or 1) |

Note: When serializing to URL, the app uses the preferred short names (seed, geom, strokes) for readability, but accepts all aliases when reading from URLs.

# Set geometry to fling

?geom=fling

# Full configuration example

?seed=my-custom-seed&geom=fling&p=1200&fp=25&dir=0.8&an=5.2&sz=900&fs=220

# Using long names

?geometry=spray&seed=test&strokes=3&packets=1500

You can programmatically construct URLs or modify existing ones. The app reads all URL parameters on page load and merges them with defaults, applying geometry-specific adjustments when needed.

bun run buildThe built files will be in the dist directory.

bun run previewThis document explains the math and code behind the splotch generator. We'll start with the foundational concepts, build up the rendering pipeline, and then explore how each geometry mode creates different visual effects.

- Deterministic Randomness

- The Density Field

- Depositing Paint: Gaussian Splats

- The Physics Simulation

- Contour Extraction: Marching Squares

- Path Smoothing: Chaikin's Algorithm

- Geometry Modes

The entire system is built on deterministic randomness—given the same seed string, you'll always get the exact same output. This is crucial for reproducibility.

We use two functions working together: xmur3 (a hash function) and sfc32 (a pseudo-random number generator).

xmur3 takes a string and produces a sequence of 32-bit integers:

function xmur3(str: string) {

let h = 1779033703 ^ str.length;

for (let i = 0; i < str.length; i++) {

h = Math.imul(h ^ str.charCodeAt(i), 3432918353);

h = (h << 13) | (h >>> 19);

}

return function () {

h = Math.imul(h ^ (h >>> 16), 2246822507);

h = Math.imul(h ^ (h >>> 13), 3266489909);

h ^= h >>> 16;

return h >>> 0;

};

}This hash function scrambles the input string into seemingly random numbers. The magic constants (like 3432918353) are carefully chosen to produce good statistical properties.

sfc32 (Small Fast Chaotic) takes four seed values and produces random floats between 0 and 1:

function sfc32(a: number, b: number, c: number, d: number) {

return function () {

a >>>= 0; b >>>= 0; c >>>= 0; d >>>= 0;

let t = (a + b) | 0;

a = b ^ (b >>> 9);

b = (c + (c << 3)) | 0;

c = (c << 21) | (c >>> 11);

d = (d + 1) | 0;

t = (t + d) | 0;

c = (c + t) | 0;

return (t >>> 0) / 4294967296;

};

}The >>> 0 operations ensure we're working with unsigned 32-bit integers. Dividing by 4294967296 (which is 2³²) converts to a float in [0, 1).

The makeRng function combines these to provide three useful random operations:

function makeRng(seed: string) {

const seedFn = xmur3(seed);

const rand = sfc32(seedFn(), seedFn(), seedFn(), seedFn());

const float = () => rand(); // [0, 1)

const range = (min, max) => min + (max - min) * float(); // [min, max)

const normal = () => { /* Box-Muller transform */ }; // Normal distribution

return { float, range, normal };

}Many natural phenomena follow a normal distribution (bell curve). The Box-Muller transform converts uniform random numbers into normally distributed ones:

Where U₁ and U₂ are uniform random numbers in (0, 1). This gives us a value Z that follows the standard normal distribution (mean = 0, standard deviation = 1).

const normal = () => {

let u = 0, v = 0;

while (u === 0) u = float(); // Avoid ln(0)

while (v === 0) v = float();

return Math.sqrt(-2.0 * Math.log(u)) * Math.cos(2.0 * Math.PI * v);

};This is essential for creating realistic, organic-looking distributions of paint droplets.

The core data structure is a 2D density field—a grid of floating-point values representing how much "paint" has accumulated at each pixel.

class Field {

w: number; // width

h: number; // height

data: Float32Array;

constructor(w: number, h: number) {

this.w = w;

this.h = h;

this.data = new Float32Array(w * h);

}

}The field uses a flat array with row-major indexing:

This means position (x, y) maps to array index y * w + x. The get and add methods handle bounds checking:

idx(x: number, y: number) {

return y * this.w + x;

}

get(x: number, y: number) {

x = clamp(x, 0, this.w - 1);

y = clamp(y, 0, this.h - 1);

return this.data[this.idx(x, y)];

}

add(x: number, y: number, v: number) {

if (x < 0 || y < 0 || x >= this.w || y >= this.h) return;

this.data[this.idx(x, y)] += v;

}The simulation uses a larger internal field (7× the display size) to prevent clipping:

const displayW = params.fieldSize;

const workingW = displayW * 7;

const field = new Field(workingW, workingW);This buffer zone allows paint to spread without hitting boundaries, then gets cropped/transformed for the final output.

When a paint droplet hits the surface, we don't just color a single pixel—we distribute the paint according to a Gaussian (bell curve) function.

A 2D Gaussian centered at the origin looks like:

Where σ (sigma) controls the spread. At the center (0,0), G = 1. As you move away, the value falls off exponentially.

The depositGaussian function creates circular paint splats:

function depositGaussian(field: Field, p: Vec2, radius: number, amount: number) {

const r = Math.max(1, Math.floor(radius));

const x0 = Math.floor(p.x);

const y0 = Math.floor(p.y);

const sigma2 = (radius * radius) / 2; // Sets denominator to r²/2, effectively σ = r/2

for (let dy = -r; dy <= r; dy++) {

for (let dx = -r; dx <= r; dx++) {

const dd = dx * dx + dy * dy; // Distance squared

const w = Math.exp(-dd / Math.max(1e-6, sigma2));

field.add(x0 + dx, y0 + dy, amount * w);

}

}

}The weight w follows:

This creates a soft, circular blob of paint centered at position p.

For fling mode, we need elliptical deposits that stretch along the direction of motion. This requires rotating and scaling the coordinate system:

function depositAniso(field, p, major, minor, angle, amount) {

const ca = Math.cos(angle);

const sa = Math.sin(angle);

const sMajor2 = (major * major) / 2;

const sMinor2 = (minor * minor) / 2;

for (let dy = -R; dy <= R; dy++) {

for (let dx = -R; dx <= R; dx++) {

// Rotate into the ellipse's coordinate system

const xr = dx * ca + dy * sa;

const yr = -dx * sa + dy * ca;

// Apply different scales to each axis

const e = (xr * xr) / sMajor2 + (yr * yr) / sMinor2;

const w = Math.exp(-e);

field.add(x0 + dx, y0 + dy, amount * w);

}

}

}The math here involves:

- Rotation: Transform (dx, dy) by angle θ:

- Elliptical Gaussian:

The major axis is aligned with the paint's velocity direction, creating streaky deposits.

Each paint "packet" undergoes a simplified physics simulation before depositing on the surface.

Each packet has:

- Position:

p = {x, y}(horizontal position) - Height:

z(vertical distance from surface) - Velocity:

v = {x, y}(horizontal velocity) - Vertical velocity:

vz

for (let s = 0; s < steps; s++) {

// Apply drag (air resistance)

v = mul(v, 1 - params.drag * dragGain * 0.25 * dt);

vz *= 1 - params.drag * dragGain * 0.35 * dt;

// Apply gravity

vz -= 1.4 * dt;

// Update position

p = add(p, mul(v, physW * 0.015 * dt));

z += vz * dt;

// Check for impact

if (z <= 0) {

impacted = true;

break;

}

}Drag: Air resistance slows the packet. Each timestep, velocity is multiplied by a factor less than 1:

Gravity: Vertical velocity decreases each step:

Position Update: Basic kinematics:

After impact, paint continues to move along the surface. A flow field simulates this:

function surfaceFlow(p: Vec2): Vec2 {

const u = (p.x - center.x) / (physW * 0.5);

const v = (p.y - center.y) / (physW * 0.5);

const radial = norm({ x: u, y: v });

const tang = { x: -radial.y, y: radial.x };

const f1 = mul(flowDir, 0.65); // Global flow direction

const f2 = mul(tang, swirl * 0.55); // Swirling motion

const f3 = mul(radial, -0.25); // Inward pull

return add(add(f1, f2), f3);

}This creates organic, paint-like spreading with:

- A dominant flow direction (randomly chosen per seed)

- Swirling/circular motion

- Slight inward contraction

Once the density field is complete, we need to convert it to a vector path. Marching Squares is a classic algorithm for finding contours in 2D data.

For each 2×2 cell of pixels, we look at which corners are above/below the threshold:

for (let y = 0; y < h - 1; y++) {

for (let x = 0; x < w - 1; x++) {

const v00 = field.get(x, y);

const v10 = field.get(x + 1, y);

const v11 = field.get(x + 1, y + 1);

const v01 = field.get(x, y + 1);

// Create a 4-bit index based on which corners exceed threshold

let idx = 0;

if (v00 >= threshold) idx |= 1; // bit 0

if (v10 >= threshold) idx |= 2; // bit 1

if (v11 >= threshold) idx |= 4; // bit 2

if (v01 >= threshold) idx |= 8; // bit 3

// idx now encodes one of 16 possible configurations

}

}Each configuration tells us which edges the contour crosses. The index is a 4-bit number where each bit represents a corner:

- Bit 0 (value 1): top-left (v00)

- Bit 1 (value 2): top-right (v10)

- Bit 2 (value 4): bottom-right (v11)

- Bit 3 (value 8): bottom-left (v01)

A filled circle (●) means that corner is above the threshold.

The contour crosses an edge when the two corners on that edge have different states (one above threshold, one below). We label the four edges as:

e0 (top)

┌─────┐

e3 │ │ e1

│ │

└─────┘

e2 (bottom)

- e0: top edge (between v00 and v10)

- e1: right edge (between v10 and v11)

- e2: bottom edge (between v01 and v11)

- e3: left edge (between v00 and v01)

For each case, we interpolate the crossing points on the relevant edges, then connect them with line segments. The case number directly determines which edges to connect via a lookup table.

Example: Case 1 has only the top-left corner above threshold (● ○ / ○ ○). The contour must cross edges e3 (left) and e0 (top) to separate the "inside" corner from the "outside" corners. So we draw a segment connecting the interpolated points on e3 and e0.

The 16 cases are:

Row 1: Four corners (single corner above threshold)

Case 1: ● ○ Case 2: ○ ● Case 4: ○ ○ Case 8: ○ ○

○ ○ ○ ○ ● ○ ○ ●

(top-left) (top-right) (bottom-right) (bottom-left)

Row 2: Four edges (two adjacent corners above threshold)

Case 3: ● ● Case 6: ○ ● Case 12: ○ ○ Case 9: ● ○

○ ○ ○ ● ● ● ● ○

(top edge) (right edge) (bottom edge) (left edge)

Row 3: "All but" cases (three corners above threshold)

Case 14: ○ ● Case 7: ● ● Case 11: ● ● Case 13: ● ○

● ● ○ ● ● ○ ● ●

(top-left) (bottom-left) (bottom-right) (top-right)

Row 4: Special cases (empty, saddles, full)

Case 0: ○ ○ Case 5: ● ○ Case 10: ○ ● Case 15: ● ●

○ ○ ○ ● ● ○ ● ●

(empty) (saddle) (saddle) (full)

Saddle points (cases 5 and 10) are ambiguous—they have two diagonally opposite corners above threshold. We resolve this by checking the center value: if the center is above threshold, we connect the two "inside" edges; otherwise, we connect the two "outside" edges.

Once we have the case number (0-15), we use a switch statement to determine which edges to connect. The algorithm interpolates crossing points on all potentially relevant edges, then connects them based on the case:

// Interpolate crossing points on all four edges

const e0 = interp(p00, p10, v00, v10); // top edge

const e1 = interp(p10, p11, v10, v11); // right edge

const e2 = interp(p01, p11, v01, v11); // bottom edge

const e3 = interp(p00, p01, v00, v01); // left edge

switch (idx) {

case 1: // top-left only: connect left and top

case 14: // all but top-left: same pattern (inverted)

addSeg(e3, e0);

break;

case 2: // top-right only: connect top and right

case 13: // all but top-right: same pattern (inverted)

addSeg(e0, e1);

break;

// ... etc

}Notice that complementary cases (like 1 and 14) produce the same edge connections—this is because inverting all corners flips "inside" and "outside" but follows the same edge pattern.

For each case, we generate line segments connecting edge crossing points.

When the contour crosses an edge, we interpolate to find the exact crossing point:

function interp(p1: Vec2, p2: Vec2, v1: number, v2: number) {

const t = (threshold - v1) / (v2 - v1);

return { x: lerp(p1.x, p2.x, t), y: lerp(p1.y, p2.y, t) };

}If v1 = 0.2, v2 = 0.8, and threshold = 0.5:

So the contour crosses exactly halfway between the two corners.

After collecting all segments, we stitch them into closed polygons by matching endpoints:

const eps = 1e-3;

const key = (p: Vec2) => `${Math.round(p.x / eps)}:${Math.round(p.y / eps)}`;

// Build adjacency map

for (const s of segs) {

segMap.get(key(s.a))!.push(s);

segMap.get(key(s.b))!.push(s);

}

// Walk segments to form polygons

for (const s0 of segs) {

if (used.has(s0)) continue;

const poly: Vec2[] = [s0.a, s0.b];

// ... follow connected segments until loop closes

}The raw marching squares output is jagged. Chaikin's algorithm smooths it by repeatedly cutting corners.

For each pair of adjacent points, create two new points at 25% and 75% along the edge:

function chaikinSmooth(poly: Vec2[], iterations: number) {

for (let it = 0; it < iterations; it++) {

const out: Vec2[] = [];

for (let i = 0; i < pts.length; i++) {

const p0 = pts[i];

const p1 = pts[(i + 1) % pts.length];

const q = { x: lerp(p0.x, p1.x, 0.25), y: lerp(p0.y, p1.y, 0.25) };

const r = { x: lerp(p0.x, p1.x, 0.75), y: lerp(p0.y, p1.y, 0.75) };

out.push(q, r);

}

pts = out;

}

return pts;

}Visually:

Before: A ●──────────────────────● B

After: A ●───● Q R ●──────────● B

(25%) (75%)

Each iteration doubles the point count and rounds corners. After 2-3 iterations, sharp corners become smooth curves.

Now we can explore how each geometry mode creates different distributions of paint packets.

The simplest mode. Packets originate from a small circular region with random velocities in all directions.

if (params.geometry === "circle") {

const ang = rng.range(0, Math.PI * 2); // Random angle

const r = Math.abs(rng.normal()) * (physW * 0.06); // Distance from center (normal dist)

const p = add(center, { x: Math.cos(ang) * r, y: Math.sin(ang) * r });

const vdir = rot({ x: 1, y: 0 }, rng.range(0, Math.PI * 2)); // Random velocity direction

const v = mul(vdir, speed);

return { p, v, vz };

}Key characteristics:

- Position: Normally distributed distance from center (most packets near center)

- Velocity: Uniformly random direction

- Result: Symmetric, roughly circular blobs

The math:

Position uses polar coordinates with normally-distributed radius:

The absolute value of the normal distribution (folded normal) ensures positive radii while keeping most packets concentrated near the center.

Packets are distributed along a line segment, with velocity biased in the line's direction.

if (params.geometry === "line") {

const ang = (params.sprayAngleDeg * Math.PI) / 180;

const dir = { x: Math.cos(ang), y: Math.sin(ang) };

const perp = { x: -dir.y, y: dir.x }; // Perpendicular direction

const t = rng.range(-0.5, 0.5); // Position along line

const lineLen = physW * (0.05 + params.sprayMagnitude * 0.19);

const alongOffset = t * lineLen;

const perpOffset = rng.normal() * (physW * 0.02); // Slight spread

const p = add(center, add(mul(dir, alongOffset), mul(perp, perpOffset)));

// Velocity with directional bias

const drift = params.sprayMagnitude * 1.8;

const v = add(mul(dir, drift + baseSpeed), mul(perp, rng.normal() * 0.2));

return { p, v, vz };

}Key characteristics:

- Position: Uniformly distributed along a line with small perpendicular jitter

- Velocity: Biased along the line direction

sprayMagnitudecontrols both line length and velocity strength- Result: Elongated splats with directional character

The math:

The line is parameterized by t ∈ [-0.5, 0.5]:

Where:

- L = line length

- d̂ = direction unit vector

- n̂ = perpendicular unit vector

- ε ~ N(0, σ) = small perpendicular noise

The perpendicular vector is computed by rotating 90°:

The most configurable mode. Creates a Gaussian cloud of packets with controllable spread and directionality.

if (params.geometry === "spray") {

const ang = (params.sprayAngleDeg * Math.PI) / 180;

const dir = { x: Math.cos(ang), y: Math.sin(ang) };

const perp = { x: -dir.y, y: dir.x };

const cov = clamp(params.sprayCovariance, 0, 1);

// Anisotropic spread based on covariance

const alongStd = baseStd * (1 + 2.2 * cov); // More spread along direction

const perpStd = baseStd * (1 - 0.55 * cov); // Less spread perpendicular

const meanShift = params.sprayMagnitude * (physW * 0.14);

const along = rng.normal() * alongStd + meanShift * (0.25 + 0.75 * rng.float());

const across = rng.normal() * perpStd;

const p = add(center, add(mul(dir, along), mul(perp, across)));

// Velocity also anisotropic

const drift = params.sprayMagnitude * 2.2;

const v = add(

mul(dir, drift + rng.normal() * speed * (0.55 + 0.65 * cov)),

mul(perp, rng.normal() * speed * (1.05 - 0.7 * cov))

);

return { p, v, vz };

}Key parameters:

sprayAngleDeg: Direction of the spray (0-360°)sprayMagnitude: How far forward the cloud shifts, and velocity bias strengthsprayCovariance: How stretched vs circular the distribution is

The math:

Spray uses a bivariate normal distribution with different variances along and perpendicular to the spray direction:

The covariance parameter interpolates between circular (cov=0) and elongated (cov=1):

When covariance is high:

σ_alongincreases → more spread along the directionσ_perpdecreases → less spread perpendicular- Result: Elongated, comet-like distributions

Center compensation:

To keep the splotch visually centered, the origin is shifted opposite to the spray direction:

const offsetAmount = params.sprayMagnitude * physW * 0.35;

center = {

x: workingW / 2 - Math.cos(ang) * offsetAmount,

y: workingW / 2 - Math.sin(ang) * offsetAmount,

};The most complex and expressive mode. Simulates paint being flung from a brush with multiple correlated strokes.

Unlike other modes that treat each packet independently, fling groups packets into strokes:

const strokeCount = params.geometry === "fling"

? Math.max(1, Math.floor(params.strokes))

: 1;

const packetsPerStroke = Math.max(1, Math.floor(params.packets / strokeCount));

for (let i = 0; i < params.packets; i++) {

const strokeIdx = Math.floor(i / packetsPerStroke);

// ... packets in the same stroke share characteristics

}Each stroke has a base angle derived deterministically from the seed:

const baseAng = (xmur3(`${params.seed}::stroke::${strokeIdx}`)() / 4294967296) * Math.PI * 2;The directionality parameter controls how tightly packets cluster around the stroke's main direction:

function sampleAngle(mu: number) {

const k = clamp(params.directionality, 0, 1);

if (k < 1e-6) return rng.range(0, Math.PI * 2); // Uniform when k=0

const sigma = lerp(1.35, 0.08, k); // Narrow when k=1

return mu + rng.normal() * sigma;

}The math:

This approximates a von Mises distribution (the circular equivalent of a normal distribution):

- When

directionality = 0: σ = 1.35 radians (≈77°), nearly uniform - When

directionality = 1: σ = 0.08 radians (≈4.6°), very concentrated

Packets don't all start from the same point. They're distributed across a small "brush footprint":

function sampleBrushOrigin(dir: Vec2) {

const perp = { x: -dir.y, y: dir.x };

const brushWidth = physW * 0.1;

const along = physW * 0.1;

const u = rng.range(-0.5, 0.5); // Position across brush

const v = rng.range(-0.5, 0.5); // Position along brush

return add(center, add(mul(perp, u * brushWidth), mul(dir, v * along)));

}This creates a rectangular "source region" oriented along the stroke direction.

Fling uses a heavy-tailed distribution for velocity magnitude—occasionally generating very fast packets:

const heavy = Math.abs(rng.normal());

const power = params.flingPower

* (0.75 + 0.65 * rng.float())

* (1 + 0.9 * heavy * heavy);The math:

The heavy factor follows a folded normal distribution. Squaring it creates heavy tails:

Since |N(0,1)|² follows a chi-squared distribution with 1 degree of freedom, this occasionally produces values much larger than the mean, creating dramatic long splatter streaks.

Fling uses elliptical (anisotropic) deposits instead of circular ones:

if (params.geometry === "fling") {

const maj = coreR * lerp(1.0, 2.6, clamp((aniso - 1) / 7, 0, 1)) * (0.9 + 0.4 * sp);

const min = coreR * lerp(1.0, 0.65, clamp((aniso - 1) / 7, 0, 1));

depositAniso(field, p, maj, min, ang, coreAmt);

}The anisotropy parameter controls the major/minor axis ratio:

anisotropy = 1: Circular deposits (major = minor)anisotropy = 8: Highly elongated deposits (major ≈ 2.6× minor)

The angle ang aligns the ellipse with the velocity direction:

const ang = Math.atan2(tangent.y, tangent.x);Fling runs more surface-sliding steps and with decay:

const slideSteps = Math.floor(lerp(12, 38, clamp(params.tail, 0, 1.6) / 1.6));

for (let t = 0; t < slideSteps; t++) {

// ... surface flow simulation ...

if (params.geometry === "fling") {

const decay = Math.exp(-t / Math.max(1, slideSteps * 0.65));

const maj = rr * (1.2 + 2.4 * decay) * (0.7 + 0.8 * sp);

const min = rr * (0.45 + 0.25 * decay);

depositAniso(field, ps, maj, min, ang, aa * decay);

}

}The math:

The exponential decay creates naturalistic fading trails:

Where τ (tau) is about 65% of the total slide steps. This means:

- At t=0: decay = 1.0 (full intensity)

- At t=τ: decay ≈ 0.37

- At t=2τ: decay ≈ 0.14

Both the deposit amount and the ellipse elongation decrease with the decay factor, creating tapered tails.

Additional scattered droplets break off during the tail phase:

const splatP = 0.12 + 0.08 * (1 - params.viscosity)

+ 0.1 * clamp(params.tailDroplets, 0, 2);

if (rng.float() < splatP) {

const a2 = rng.range(0, Math.PI * 2);

const dist2 = coreR * rng.range(0.9, 5.2) * impactEnergy * (0.7 + 0.6 * sp);

const ps2 = add(ps, { x: Math.cos(a2) * dist2, y: Math.sin(a2) * dist2 });

// ... deposit small anisotropic splat at ps2 ...

}The tailDroplets parameter increases the probability and spread of these secondary droplets, creating the characteristic scattered-droplet look of real flung paint.

The rendering pipeline transforms a seed string into an SVG through these stages:

- Seed → RNG: Deterministic random number generator

- Geometry sampling: Create initial packet positions and velocities

- Physics simulation: Ballistic flight with drag and gravity

- Impact & deposition: Gaussian/anisotropic paint splats

- Surface flow: Post-impact spreading and streaking

- Field processing: Blur and normalization

- Marching squares: Convert density field to polygons

- Chaikin smoothing: Refine jagged contours

- SVG generation: Export as vector path

Each geometry mode customizes step 2 (how packets are distributed) while sharing the same downstream pipeline, creating distinctly different visual results from the same physics engine.

- Deterministic generation based on seed strings

- Multiple geometry modes: spray, fling, circle source, line strike

- Real-time preview with density field visualization

- SVG export with customizable size and placement

- Batch export of variations as ZIP file

- Extensive parameter controls for fine-tuning the splat appearance